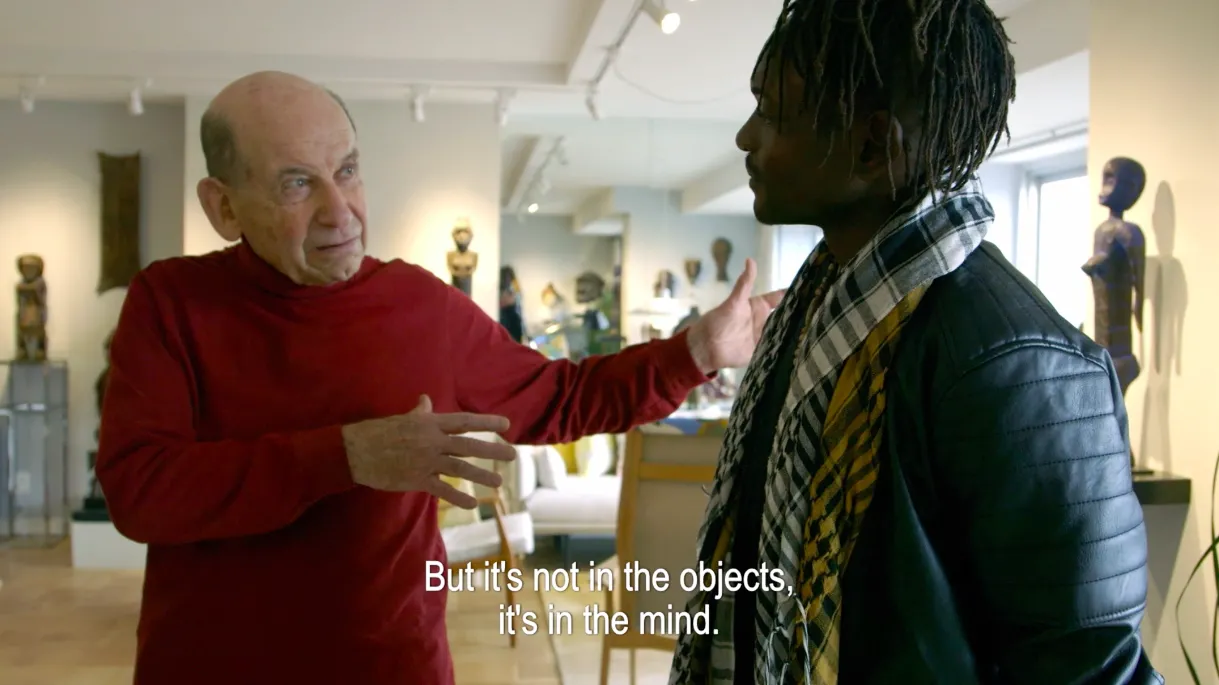

The conversation delves into the implications of owning cultural artifacts. Weiss says that the seller made the choice between holding on to a physical object or being able to send his children to school. He agrees that he has elements of Cedart and Matthieus history that they need, but he proposes that it is not about physical objects, it’s about the mind. If the sculpture would be returned, what would happen to it? There would be quarrels between those for whom the sculpture is a spiritual object and those who say it should be in a museum. Weiss points out that before colonization, there were no museums; objects like the Balot sculpture were living objects.

While reflecting on such dynamics, Matthieu and Ced’art stress the importance of reclaiming their own culture’s artistic creations and advocating for the return of objects, such as the Balot sculpture, as an act of resistance. The artists emphasize the significance this restitution could have, even if it means holding the sculpture only for a temporary exhibition. The episode prompts reflection on the role of museums, the value of cultural heritage, and the ongoing dialogue surrounding restitution.

Herbert Weiss co-authored “Art with Fight in It: Discovering That a Statue of a Colonial Officer Is a Power Object from the 1931 Pende Revolt” together with Zoë Strother and Richard Woodward, who are interviewed in other parts of Plantations and Museums.

Throughout part one, The Pende Revolt 1931: Oppression, Protest, Survival, and Art, Weiss discusses his arrival in the Congo, in December 1959, to study the Congo’s independence struggle. He was focused on the Parti Solidaire Africain (PSA), which successfully mobilized various ethnic groups in the Kwilu District, where the Pende population resided. The PSA became part of an alliance that won the 1960 elections and formed the first Congolese government. However, tragic events followed, including the mutiny of the army, secession of rich provinces, and Cold War competition. Patrice Lumumba, the leader of the alliance, was assassinated in 1961, leading to the expulsion of his allies.

During his research, Weiss encountered two Pende sculptures that led him to investigate the significance of the 1931 Pende Revolt. In 1972, he came across a sculpture representing a white man, identified as Maximilien Balot, who was killed in the revolt. According to their study, the sculpture was created to preserve their memory of white people, as the Pende believed they had been chased away for good.

“I think this enormous concentration on the return of physical objects is a little reactionary. It’s not in the objects. It’s in the mind”

- Herbert Weiss

According to Weiss, the Balot sculpture provided valuable evidence of Congolese anti-colonial protest. It contributed to the understanding of the Pende Revolt and its significance in shaping the history of the Pende people. The revolt marked a turning point in their struggle against colonial oppression and represented their determination to resist and assert their rights. The sculpture serves as a powerful testament to the resilience and resistance of the Pende throughout their history.

About Herbert Weiss

Herbert Weiss is a scholar who dedicated his career to studying the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) since 1959. His research has centered on crucial themes like nationalism, independence struggles, mass mobilization, protest, democratization, elections, decentralization, and the role of militia. His most influential contribution to African studies focuses on the radical protest movements within rurally-based populations in the DRC. This insight has shed light on significant historical events such as the independence struggle (1959-60), the Congo Rebellions (1963-68), and the rise of rurally based militia groups from the 1990s to the present.

Throughout his distinguished career, he has remained an active member of the African Studies Association since 1961, earning recognition, including the Herskovits Prize in 1968. In 2009, the National University in Kinshasa (UNIKIN) celebrated his fifty years of research with a two-day conference focusing on political mobilization during the 1960s.

Sources

The text on this page draws from the following source:

“Part I: The Pende Revolt 1931: Oppression, Protest, Survival, and Art” by Herbert Weiss, in “Art with Fight in It: Discovering That a Statue of a Colonial Officer Is a Power Object from the 1931 Pende Revolt.” African Arts, vol. 49, no. 1, 2016, pp. 56-60.

Further reading

Roodt, Christa. “Restitution of Art and Cultural Objects and Its Limits.” The Comparative and International Law Journal of Southern Africa, vol. 46, no. 3, 2013, pp. 286–307. JSTOR.

Savoy, Bénédicte, and Susanne Meyer-Abich. Africa’s Struggle for Its Art: History of a Postcolonial Defeat. Princeton University.